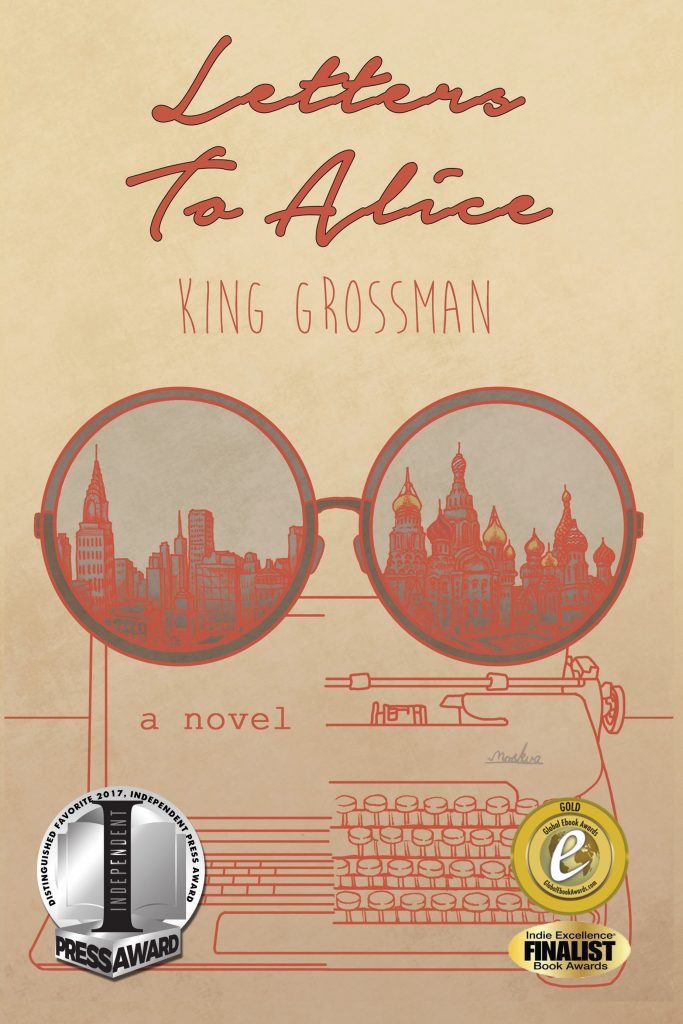

Letters To Alice

Published: November 21, 2016

Genres: Literary Fiction

Editions:

Paperback: $ 16.00 USD

ISBN: 978-0997670899

Pages: 436

This lyrically written novel gives you Frazier Pickett III, the “slumbering man.” He has taken up looking over the top of fake reading glasses. His dirty little secret: He’s desperately myopic, actually preferring not to clearly see what’s going on.

Having penned three unpublished manuscripts, the slumbering man hasn’t written anything in over four years, nor has he been to a street protest to push back against endless warring, climate change, economic injustice, or just name any number of movements of which he used to be on the front lines. Margaret, his wife, tunes him out as much over his worsening condition as her angst in not being able to find the courage to pen the novel she dreams of writing. In need of muses, while Margaret distantly awaits him to be hers, the slumbering man falls for the beautiful French contemporary artist Anastasie Moreau.

Letters To Alice also tells the story of Katya Ivashov, Boris Pasternak’s young writing protégé, who inspires Pasternak to get his manuscript for Doctor Zhivago smuggled out of Russia for publication in the West, risking their lives. What does this have to do with ending Frazier’s slumber or perpetuating it and, what’s more, who is Alice?

Reviews:

Editorial Professional Reba Hilbert wrote:

The lives and loves of these characters intertwine in this richly layered novel that delivers a thoroughly delightful surprise of an ending. King Grossman is a poet, with exquisite, evocative language, and Letters To Alice is a rich read that will leave you examining your own soul for greatness.

Kirkus Review wrote:

Grossman writes with enough spirit and optimism that the novel’s complex, likable characters have room to flourish… An ardent, well-told story that manages to connect Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, and Doctor Zhivago.

Click Here To Read An Excerpt:

CHAPTER ONE… He was a slumbering man. Not a sleepwalker, or awake, slumbering, eyelids droopy to the world, all its corruption, its death march with violence and bad religion, the corporatocracy pulling all the strings, a non-conspiracy, conspiracy of bloated power, where things just happened, and bombs were dropped, and oceans were poisoned, and people of the land were pushed off their land, and so much more doggerel went down in the name of “human progress,” which really meant flowing all the money up to the top until, what? ten rich guys in New York City, who weekend in the Hamptons and summer in Aspen, have 99 percent of it—to hell with the planet—to hell with 7,000,000,000 everybody elses.

This great white whale, this Moby Dick, was so big who was going to stop it? Nobody could turn things around now. And that’s why he slumbered purposefully, and with exuberant style. That, and he had a job to keep, a family to be a partner in feeding, a reputation that had never been built.

To assist him in this endeavor, he had a secret weapon. At all times the world looked sparkly, tree branches wore bangles, lights were stars, the sun furry, the moon a giant pearl, and most importantly people’s faces appeared nondescript, their features flattened like people in a Georges Seurat painting. At all times, that is, unless he chose to see things clearly, but doing that was mostly too angering or depressing, often triggering a one-two punch of both monkeys-on-the-back, so he usually used his secret weapon. At first he thought all those years working as an editor for a third-rate literary agent, poring through poorly written manuscripts under bad fluorescent light, had stolen something from him. Then, as things kept getting worse, he realized it all had been a gift, and ultimately a secret weapon of protection. He sort of fell into this realization, actually.

He had been walking along the street, on his way back to the office after a quick Subway meatball sandwich for lunch, when a group of four pretty snarly-looking guys hemmed him in in the alleyway he regularly used as a shortcut. They demanded all the money he had on him, which he handed over without protest. The one with the fewest visible tattoos, to this day still striking him with a certain irony, reared back to take a swing at him. Which he returned in kind, surprising himself with his dexterity and strength. His fist swooshed through the air right in front of his assailant’s retreating nose, as the blow coming at him glanced off his shoulder. He tumbled backward onto his not overly meaty butt, which pinged with pain a hell of a lot worse than his shoulder. They laughed at him, and while they did, they seemed like fuzzy caricatures of people incapable of being taken seriously. He laughed back at them nervously, and then from the belly. “F- you, man,” one of the young men grumbled. He laughed harder as they turned and ran. This was a new way of seeing the world or, for that matter, not seeing it. And he liked the effect. Gone were his humiliation and anger. Not gone, but covered over with a warm, fuzzy Christmas-y feeling he hated; flashes which would always show up during the holiday season, but this was like one long flash along with a hit of Percocet to add just the right amount of I-don’t-give-a-shit. Besides, it was June. Reaching over, he picked up his eyeglasses, which had come off with the fall. The right lens was cracked, the left ground into pieces on the concrete. His muggers had stomped on them. “Thanks,” he muttered, stuffing the black horn-rim frame in his jacket pocket. As he stood up and brushed himself off, he devised the greatest plan ever for his life.

Okay, fine, in the month before he had become desperately nearsighted. Myopia. A rare almost sudden onset of it. His pride had kept this a secret, even from his wife Margaret and their two kids. But then they were always so busy with their lives, it hadn’t been hard to pull off. The ophthalmologist had assured him the condition was hereditary, but he suspected all the editorial work in harsh lighting had done in his eyesight. Whatever. Myopic, he had just found out, was his preferred way to see. He would go back to the optometrist who had fitted him with the beefy horn rims, and choose slim reading-glass frames. That way he could look over the top of them and remain in this I-don’t-give-a-shit-fuzzed-out-on-Percocet world all the time he wanted. That’s how his myopia became the mainstay of slumbering. And he had gotten good at it.

Don’t get this wrong, he had no illusions of grandeur, wasn’t in a position to change much, never had been, never would be, but still if there were just some people, anybody really, at the top worth following, or enough underneath to follow well, then maybe it would be worthwhile not to go around like this. What were we leaving to our children and grandchildren? Yes, everything mattered so much more once Mattie and Doug came out of Margaret. That had been a trip, there in the delivery room witnessing the miracle of life. A very good trip. It had taken his breath away. But life was fast, too fast to keep up with each other. Their family had gone all Cat’s in the cradle, and the silver spoon. So it wasn’t only what was missing from afar that had worn him down; love seemed to be nothing more than a word nibbled on like a piece of stale toast until it had been totally consumed with a belch.

He thought of the word symbiotic when he thought of what he and Margaret had together. It remained an unspoken word between them that had grown like a malignancy. Was there love underneath it? He had all but stopped asking himself. Motions, going through the motions, that’s what they had sunk to doing. Oh, there was still some pretty awesome sex, and their pillow talk afterward felt intimate enough to scare him out of bed for a cigarette and coffee at the kitchen table. They spoke the L word to each other, and when they did, it didn’t feel entirely wrong. Just mostly wrong, the cancer more and more imperceptibly spreading.

When hadn’t it been that way, really? Back at NYU in the creative writing program, her prose had been the surest, the strongest, and when he finally got the courage up to ask her for a beer and sushi, her conversation had held up with her prose. Back then her eyes glimmered not with wonder, but with a certain kind of togetherness. And for the upstart, untogether novelist he was, it sure felt like falling in love. As she went to work for Harpers as a copy editor, he waited tables in the evenings so he could write all day. While she zoomed up the ladder to become a senior editor and then vice president of creative nonfiction, he stopped waiting tables and penned three manuscripts in three years. All of which were still collecting dust in the bottom of his desk drawer.

Every time he had opened that drawer and took a look at them, trying to get the spark back for writing, all the words on those pages seemed to be the only ones he’d had in him. No more were left, not any worth writing down for others to potentially read anyway. Over the past four years, since the last manuscript had been finished, he had opened that drawer less and less often. In the past six months the count was zero, a big fat goose egg.

Now, as he walked into the Javits Convention Center to attend Book Expo 2010, his job was manning the booth for Flying Pens, and what kind of name was that supposed to be for a literary agency? Go figure, he thought on approaching the booth, which he thought about most things concerning his work. He didn’t have the authority to take on new clients even if a great writer came over and bit him on the ass. That was okay, though. The role of slush pile rejectionator he had actually taken a sulky affection for. He sat down behind the poster for the outfit’s one and only best-selling author, Manny Baton. On it was a blowup of the guy’s newest pulp fiction book’s dust jacket, which looked something like a lustfully spray-painted railcar making love to an angrily spray-painted road sign. The book’s title was Graffiti Junk. He hadn’t read it, and had no plans to. The box with the actual books in it hadn’t arrived, or better yet, probably had never been ordered by Lucia, who was responsible for doing things like this in the office. So he sat there staring at all the flat faces passing him by. Maybe some of them glanced over in dismay at the pitiful state of the booth, but then he couldn’t tell. He was a slumbering man with his glasses resting on the end of his nose, eyes set above the frames.

This went really well for over two hours. The main thing he’d accomplished had been not calling Lucia to get some books delivered. And then the inevitable happened. One of those out-of-focus people approached his booth. A slender, tall man or a woman with runway model potential, he could make out that much. She or he had a fuzzy shock of blond hair that resembled wheat blown sideways in a windstorm. Jeans and some sort of loose-fitting jacket glowed as if with a bluish aura surrounding them. Infiltrating Nerdsville, a probable hipster. He looked down at his boots, through his eyeglasses. This was a refinement of the secret weapon he had developed. In sharp clarity he studied the white stitching along the soles of his brown leather work boots, up the insoles to the laces, around the eyelets for his shoestrings, the right boot, the left one, then back again. It felt like riding a train to nowhere, on an endless figure eight of track. Magnificent Solitude, Cold Isolation, Ironclad Protection were the names on the sides of its railcars.

“Pfft, this is shit.” It was said with a lilting high tone in broken English and a lovely French accent.

A woman then; a Frenchwoman. He kept looking at his boots. He could not deny the sound of her French-ness felt pleasing. There had been a time he dreamed of penning novels in an apartment along the banks of the Seine, but that had fizzled out altogether, hadn’t it. This was not a question, but a statement of fact. With or without looking through those eyeglasses, he no longer could spot the Francophile within. Somewhere along the way of getting all the rejection letters for his manuscripts, he even stopped trying to imagine such a life. Marcel Proust, Victor Hugo, Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, yes, Edith Piaf too, while he was at itbe damned.

A long silence settled between them, which would’ve been awkward had he not been on the train. It was painful enough for her, though.

She spoke to the poster, not him, when she finally went on. “Graffiti art must profound, or they’ll simply laugh it off.”

True enough… probably. But what’s the use?

“What you doing here, I mean, you work this boot?”

He picked up the speed of the figure eights with his eyes. Boot, man, he liked how the Frenchwoman clipped the h off booth, and the clarity borne by words she left out entirely. It was like how a birth mole above the lip, a slight lisp, or a misaligned tooth in the middle of a smile made those women more sexy. Not beautiful. Desirable. Imperfections drew him in only as good stories did. The odd off-center things reminded him of himself, he supposed. And with all the time in the world to think while being a slumbering man, he’d developed the theory we were attracted to things that were more like us, bad or good. Until right now, in the past four years, since he’d laid his pen down, most any human connection that mattered at all had been made with the bad stuff. His growing lethargy, cynicism, matching up with any number of women who seemed to be swimming in them too, those were the times he’d considered lighting off into affairs. No shortage of opportunity there. Not that he was overly handsome, sort of short actually, hair thinning, and he’d developed a little paunch after abandoning exercise, also about four years ago. But several of those certain types of women had played the game with him, which proved his point about pain attracting pain, and he couldn’t be sure, but it only made sense that joy attracted joy. Another thing about being a slumbering man, though, was in a reverse sort of way, it protected him against going through with an affair. He didn’t care enough to have one.

“You and I from different worlds.”

Correct-a-mundo. After all, he heard no I-don’t-give-a-shit in her tone, only music.

“Humph.”

Then, the tap of footsteps moving away on the concrete floor.

“Yeah, and what world are you from?” Why had he said this? His figure eights went to breakneck speed.

The footsteps moved closer again. “One that cares!”

Another long silence, save for the bustle of the conventiontwo worlds away.

“Look me.”

As if in some sort of spell, he did. There was her windswept hair again, her blue aura, her sloe eyes, all safely out of focus. But he no longer felt so utterly that way.

“You not look me, really. Your eyes no dead, no alive, they…what, they suspended.” She raised a hand. “I feel sorry for you.”

This was freaky aware, the first person to truly see him who knew it since he became a slumbering man. The first with enough oomph to tell him, anyway. Even Margaret had remained oblivious, especially her, he thought. A spike of redness rose in him toward Margaret. She wasn’t suspended, no, she was dead inside, or honestly, had she never cared enough to notice him? “I’m sort of a frustrated writer these days,” he said.

“You kidding, me too!”

There seemed to be a smile that went with this, but of course he couldn’t see her mouth that well.

“I am artist who use words on canvas, and more with color and black squiggles.” She indicated the poster. “I make good graffiti, not this, but I want go deeper with words. I think they go deeper now.”

“Why?” he said, surprising himself at meaning it. Evidently, a small part of him still did believe if he could’ve only gone deeper with his writing, people would’ve wanted to read it.

She sat on the edge of the table and leaned on a hand nearer him. “I have gotten good with my art. People like it.” A lighthearted chuckle. “It’s in galleries all over place. But they don’t get what have to say. I want write a book.”

“They probably won’t get that either.”

“Don’t tell me that. Art gone too professional, have less, how you say, diversity of thought.”

“I hate to burst your bubble, but it’s the same with books.” Now, he gestured at the poster. “This is what people like these days.”

She shook her head. “Not all people, not people who change world.”

“What if it’s too far gone?”

“It doesn’t matter, we do for art’s sake, because we have something needs say.”

Yes, that’s what he had thought. Why he started writing to begin with. He wanted to go back to gazing at his boots; he wanted to lower his eyes behind his fake reading-glass lenses and bring her into focus; he did neither. “Let the universe take care of the outcome, huh.”

“Something like that. Here, take card.” She reached inside the bag slung over her shoulder and between her breasts, then came out with it. “I have opening at gallery tomorrow night. You maybe come.”

He took the card and brought it close to his myopic eyes. Anastasie Moreau, he read her name written out in cursive script, underneath it the word Artist, a phone number and email address in the bottom corners. “Maybe,” he said dully.

“You hide.”

“What?”

“You read card without glasses. You no need them. You hide.”

“Maybe I will come.” He smiled crookedly, always keeping his eyes above the frames.